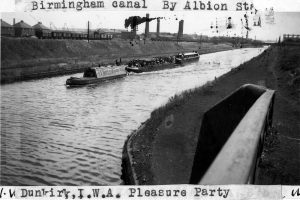

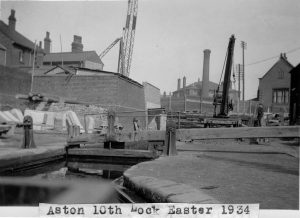

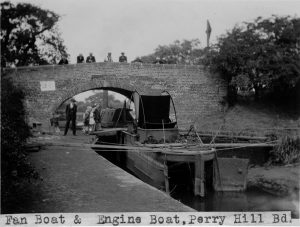

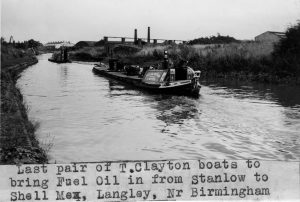

The illustrations (not necessarily related to the surrounding text!) are from the Will King collection of historic photos, and are reproduced here with kind permission.

Whilst construction started on the Birmingham Canal Navigation in 1768, plans to build a canal network to serve the West and East Midlands had been instigated more than ten years earlier. Those engaged in such promotion included the Earl of Gower and both James Brindley and John Smeaton had been involved in preparing plans for inland navigation in this region. The conflict between making rivers navigable or making a canal was a battleground during this time.

©Will King Collection.

Last but one pair to bring fuel oil in from Stanlow to Langley, Oldbury, at Brades Hall, 1956. Butty Rea.

This battleground first occupied the North East and North West of England. On the east side, the Aire and Calder and the Calder and Hebble Navigations began as river navigations to Leeds, Wakefield and Sowerby Bridge, with short canal sections to bypass weirs. John Smeaton, engineer, was responsible for the improvements up towards Sowerby Bridge. Similarly the Douglas, Mersey and Weaver became navigations to serve Wigan, Manchester and Winsford in the North West. Thomas Steers, as engineer, was particularly active here. He first was responsible for the original Docks at Liverpool, which removed the shallow “Pool” for the dock complex. He surveyed the navigation from Warrington to Manchester using the Mersey & Irwell rivers, next he surveyed the Douglas Navigation that linked the Ribble estuary with Wigan. His later and best known work was the Newry Canal, in Northern Ireland. This was the first Summit Level Canal in the British Isles, which linked Lough Neagh with the River Newry and provided the principle link of moving coal from the Tyrone coalfield to Dublin by inland waterways. This work had been started by Edward Lovett Pearce, was continued Richard Cassells and from 1736 until completion in 1741 had construction under the control of Thomas Steers and his resident engineer, William Gilbert.

A summit level canal was an artificial navigation that had a water source to the summit level. Such types of canal existed elsewhere in the World, such as the Grand Canal of China. The first canal to use pound locks had been the Briare Canal in France (completed in 1642) and later the Canal du Midi (completed 1684) was an impressive engineering scheme at 150 miles in length and was part of inland waterway link between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean. Such waterways provided the inspiration for the concept of the summit level canal and it was this idea that became the primary weapon in the war of canals and river navigation.

©Will King Collection.

Overhead crane with heavy stone. Bottom end No 10 Aston lock reconstruction, Easter 1934.

The Sankey Brook Navigation had started as a plan to make the brook navigable to St Helens from the Mersey. With Henry Berry as principle engineer, this scheme was changed to become a canal when it was found that the brook had insufficient water supply. The first part was completed in 1757 and brought coal from the collieries near Haydock down to the Sankey Brook using pound locks and with an aqueduct over the Sankey Brook north of Bewsey Lock.

An aspect of canal navigations was the requirement for infrastructure. Pound locks were integral to reaching the summit level, reservoirs or feeders were needed for water supply and aqueducts, embankments and tunnels were constructed to maintain specific levels. Weirs were also needed to run off excess water into adjoining streams and rivers. These were all features of the canal, whilst locks were the only thing in common with river navigations. River navigations also differed in the locks made. Single lock gates were once a feature on early river navigations, and pound locks were a later development. There was also the flood lock on river navigations which was closed in times of high water and at the same time prevented navigation. Canals were open all year round, and the only hinder to navigation were breaches in the embankment, ice and subsidence.

The move for inland navigation to the West Midlands industry was also dominated by river navigations. The Severn provided navigation through Bewdley and Bridgnorth, all be it hampered by low water levels and floods. The Warwickshire Avon enabled boats to reach the bridge at Stratford upon Avon, whilst the Trent was navigable as far as Burton on Trent. Although with the Trent there the Fossbrooke’s and Hayne’s that controlled navigation and made it difficult for other carriers to reach Burton. That other carriers succeeded in doing so angered the Hayne family who blocked the lock at Kings Mills and prevented passage through it for over 8 years. Such action provided good reason for an alternative means of navigation and that was the canal.

James Brindley was associated with canal surveys to Lichfield and the Potteries from the Trent in 1758 and 1759 (the second time being with John Smeaton). Josiah Wedgewood, potter of Burslem was intent on improving communication between the Potteries and the Mersey. The damage caused to his transport of pottery from his Ivy House Pottery using pack horse trains made him determined to make changes to transport. Wedgewood’s first success was with the new turnpike routes to the Potteries and then came the determination for a canal link between the Potteries and Liverpool.

Brindley at this time had been responsible for the making the Bridgwater Canal from Manchester to the Worsley Coal mines. Wedgwood and other like minded people continued to look at a canal link to the Potteries that provided not only route to the Mersey but also the Trent. Plans were being formed during 1765 for a canal to the Potteries and those plans drew on the earlier survey by Brindley and Smeaton.

©Will King Collection.

Hamstead Basin 3.6.1936. New cill and paddles basin bridge. Dredging into main canal. This levelled out later.

Thomas Bentley was also a strong advocate of the inland navigation system being proposed. Bentley as a Liverpool based merchant had an interest in a canal system which would link the Midlands to the port of Liverpool. Both he and Wedgewood played their part in soliciting the various land owners, MPs and authorities in an attempt to gain a support base which would see their proposal as the one to back. In 1765 the Grand Trunk canal was not the only inland navigation scheme being proposed, it was therefore important that Josiah gained the support of those men capable of make his own vision.

The Bill for the Trent and Mersey Canal was presented to Parliament on 18 February 1766 and authorised on 14 May 1766. This was one of two canals authorised that day. The other was the Staffordshire & Worcester Canal. James Brindley was engineer to both. He had plans for linking the Mersey, Trent, Severn and Thames by inland navigation though summit level canals. The other schemes that were too authorised were the Coventry and Oxford canals that were to form the connection between the Trent & Mersey and the Thames.

The Birmingham Canal Navigation was yet another canal that James Brindley was engineer, but with all such canal schemes under Brindley’s control, there was always a clerk of works and it was that person that had the day to day responsibility for the canal construction.